The Father Monologues – Part 3 (Billy)

“The Best Thing I have seen for a very long time”

Ingrid, Bristol, June 2008

Meet local (ex-)brickie, Billy. Best mate to Danny, and toy-boy lover to Jenny,

Billy is fighting his own quest, to find his own absent, (and certainly not black) father.

To do so, (since his own mother is so tight-lipped), he decides to try to ‘remember everything’ for himself, and visit Rajid, the regression therapist we first encounter in “Danny.”

Purely to afford Rajid’s sky-high fees, he fakes depression and enrols on the “Access to Healing” scheme, whereby an NHS psychiatrist can refer him on to an “approved alternative therapist.”

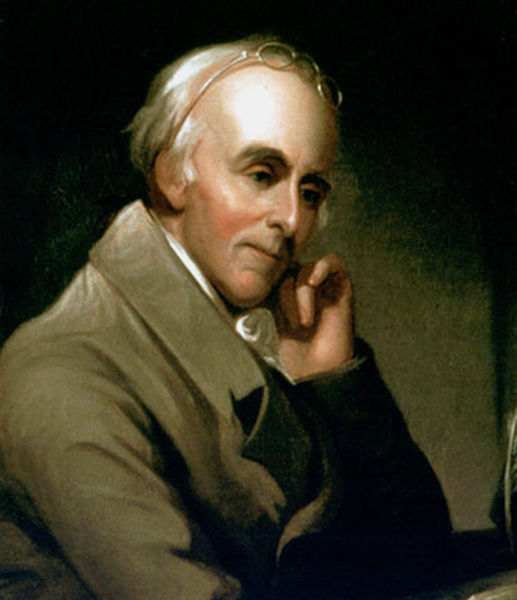

Jumping through all the wrong hoops, (but singing all the right notes), Billy finds himself stuck with Jimmy, a repressed shrink, whilst with Rajid he regresses further back than he had planned and discovers that he is none other than the eminent (and surprisingly musical) Dr Benjamin Rush, controversial Father of American Psychiatry, Founding Father of the USA and Co-signer of the Declaration of Independence.

To his concern, Billy also discovers that Jenny is not a woman; that Benjamin Rush was a son-incarcerating sadist, nicknamed Dr Vampire, (who believed all black people just had a touch of leprosy that could be “cured” with peach juice); that his mother was not raped to conceive him (as she has always so heavily implied); that his own “family doctor” might have once lived up to his epithet more closely than previously suspected; that his unbelieving shrink is living more of a lie than even HE knows; that his regression therapist has some past of his own and that Billy just like Rush’s own son, is dangerously close to being on a fast track into the new modern local flagship Prince Regent psychiatric hospital, the walls of which he himself had once helped to build!

…place him in the New World, at the end of the age of the Inquisition and the beginning of the Age of “reason”, and a time of impending war.

At age 6, take away his gunsmith father, leave him in a puritanical family, with distant, cold and pious men as mentors.

On completing his education, he travels to Edinburgh to study “medicine”.

He gradually becomes highly pious and moralistic, and on becoming a “doctor”, he “squires” women aplenty (including notably young girls), even in the days just prior to his engagement to his first fiancée, Sarah Eve, herself only 16. She herself becomes ill and dies just before their wedding, but our hero presents her parents with a bill for treating her.

He develops a distorted view of women, profusely idealising them, describing one in a long anonymous letter to a Philadelphia newspaper in impossibly favourable flowing poetic terms. After many attempts at “intimacy” (a repeated pattern of somewhat deluded infatuations), he finally settles down with the daughter of a political and business ally, and by her fathers 13 children, rarely staying home to be with any of them.

He develops a tendency to accuse those who disagree with him or threaten his growing status (as a politician and doctor) as having disorders of the mind. He starts to turn experiments on those he considers “mentally ill” into a “science”. Quickly, in a young naïve nation busy with rebuilding and easily influenced by a verbose persuasive “professional”, he obtains a mandate to build an “institution” where he can perform his experiments. There he uses contraptions and practices to punish, subdue and control his subjects, including a tranquiliser chair (a chair with hand and feet straps and metal box for the head), a gyrator contraption, (by which the subject is placed lying on a large disc, with head at the outer edge, to be spun at very high speeds), and plunging them into ice water, amongst other sadistic experiments reminiscent of both the Inquisition (that openly he eschews) and of the Nazi death camps to come.

He rails against the British and the “arbitrary rule” of the “mad” King George, urging insurgence against them, including circulating leaflets on how to make the gunpowder to wage it.

He’s nicknamed “Doctor Vampire” throughout the colonies for his persistent use of the long outmoded bleeding of patients during several yellow fever epidemics throughout the Philadelphia region. Many die as a result of the bleeding, and he is constantly attacked for his practices.

He speaks against slavery, but for uncertain reasons. He believes blacks to be simply white people who have leprosy. He presents a long paper on this very theory to his (rather astounded) colleagues of the American Philosophical Society.

In 1812 he presents his opus magnum, his thesis on “Diseases of the Mind”, as thin in logic as his theories on Blackness. Rather than own and accept his own wide range of human desires, emotions and mental processes, they become part of his own list of what constitutes insanity, including homosexuality, onanism (masturbation), and malingering, to name but a few.

He continues to see everything in terms of mental health or illness, describing all kinds of (to his eyes) social undesirable conducts as the manifestation of mental disorder. Those opposed to his views are invariably sick, those who oppose the American Revolution suffer from “revolutiona”, women who support it are cured of “hysteria”.

Although he often himself lies as a “treatment” for his subjects, for lying as a disease, he extols, “bodily pain, inflicted by the rod, confinement, abstinence from food.” In his many hundreds of letters, leaflets, pamphlets, articles, and papers he very briefly alludes to one particular period of youthful “weakness” of his own, but never divulges what this weakness was.

Through the “practices” he begins justifying as “scientific method”, many versions of activities of the recently defunct inquisition remain in place, but are simply renamed in “scientific” language.

His eldest child, seems (as one might expect under such a proponent of psychiatric imperialism) to struggle to develop an identity of his own. The young firebrand son, John, oscillates between practicing “medicine” under his controlling father, and serving as a Naval Officer against the British. Then in 1807, after many conflicts, some seemingly connected with the wave of feeling against his own father, the son kills his own best friend, Lieutenant Benjamin Taylor, in a duel.

The Father, now Philadelphia’s leading doctor opens the first Hospital for the Mentally ill, and promptly puts his own son into it. In 1813, the father dies, leaving his son, to die in the “hospital” about 40 years later.

Throughout his life the father seems to show a repeated pattern of avoiding intimacy, always busy with politics at every level, being highly verbose with copious (oft written) opinions about every aspect of other people’s lives. He commentates on life, aiming to control it rather than participate in it.

Could it be that losing his own father at 6 years old, or of having never really experienced intimacy as a child sets the pattern for a man who, whilst avoiding intimacy himself, insists on knowing the most intimate workings of humans through his “work”, without ever having to be vulnerable himself. Who knows? This is just a story.

Can this be the “Father” of American Psychiatry, Founding Father of the USA, co-signer of the American Declaration of Independence, and the man whose face still adorns the Seal of the American Psychiatric Association?

——–

In his two books “The Manufacture of Madness”, and “The Myth of Mental Illness”, Dr Thomas Szasz, dismantles the credibility of the mental health industry by exposing and deconstructing the mythology, history and language of both it, and of one of its “founders” Dr Benjamin Rush.

Read any standard biography on Rush, oft penned by proponents of the political right, of the right wing elements of the Church, of versions of US patriotism or by those heavily invested in the validity of a burgeoning mental health industry and it’s use as a tool of social control, and you’ll find stories galore of his heroism.

But dig deeper. What is unsaid…. is also interesting.

Written and Performed by Jonathan Brown

Music arranged and performed by Raffaele Bizzoca (www.myspace.com/lelebizzoca)

Lyrics and original melodies by Jonathan Brown

(with many original words from the writings of Benjamin Rush)

Directing help: Juliet Larken and Strat Mastoris

Technical, Light & Sound: Kimberly Turner, Clive Hedger (Sussex)

Pete Gioconda, Chris Dixon (Bristol)

Debbie Bray (Devon)

Thanks also to Bridgwater Arts Centre for support (www.bridgwaterartscentre.org.uk)

Voice coaching help: Thanks to Sylvia Sturtevant.

is dedicated to Arthur Miller who died in 2005.